On 29 March, 2000, the domain name digitalviolin was registered and a very small website started life, hosted via Freezone. It set out to be a dynamic online publication, detailing what then was a very little known subject: the history of the electric violin.

Digitalviolin was authored using basic HTML and presented for the first time in any real detail the movers and shakers responsible for the development of a successful, fully electrified violin.

Within the first year online, digitalviolin received two web awards: The Informative Music Site and the Golden Web Awards.

Research into the subject had begun in Manchester in the early 1990s; very simply at first, gathering adverts and articles found in books, periodicals and magazines stored in both the Royal Northern College of Music Library and Manchester City Central Library. Practical research, in terms of playing and exploring electric violin technique was pursued by exploring the instruments and technology available via the two music instrument shops retailing electric violins – Johnny Roadhouse and the now defunct A1 Music.

By 1995 however, the all new Internet cafe gave access to a new resource and the discovery was made of the then named Digitalrain domain, hosting a site called Bowed Electricity. This was a real catalyst for the research. The site’s author John Schussler had gathered together a few photos and nuggets of information that were a direct insight into a history of the electric violin dating back to the 1930s. A revelation being that three of the biggest names in the field of electric guitars: National, Rickenbacker and Fender had also made electric violins. This information flew in the face of establishment held view that the subject was too new to be able to study.

Questions immediately sprang to mind: “where were these oldest electric violins”, “who played them” and “were they recorded”?

Over the course of the next two years, spending many hours returning to the same libraries but now armed with much more specific search criteria, a seeming wealth of dormant information was uncovered and collated. Seemingly too though, the actual instruments from the earliest period had disappeared.

In an attempt to broaden interest in this quest, in August 1997 the first draft of what eventually became known as “Digital Violin” was committed to paper. At the time it represented the only printed study of its kind and was endorsed by the Head of Secondary Music Education at Manchester Metropolitan University, noted as being an important new document. However, cost of paper printing inhibited a traditional publication, so experiments began with the possibilities of creating a dynamic and interactive digital publication. By 1998, proof of sorts that the subject of electric violins was gathering serious interest came with news of the imminent publication of Hanno Graesser and Andy Holliman’s joint work, “Electric Violins” (Verlag Erwin Bochinsky).

Upon publication it was obvious that there was much still to say, especially about the earliest history, particularly in terms of makers. Digital Violin had already sourced, collated and reviewed much more than was presented in the book. And, it still appeared that no-one had turned up the whereabouts of surviving instruments. The decision was made to join the rapidly expanding world of “dot-coms” by translating the work into a website. Holliman described what then appeared on the newly established digitalviolin.com site as a “Magnum Opus”.

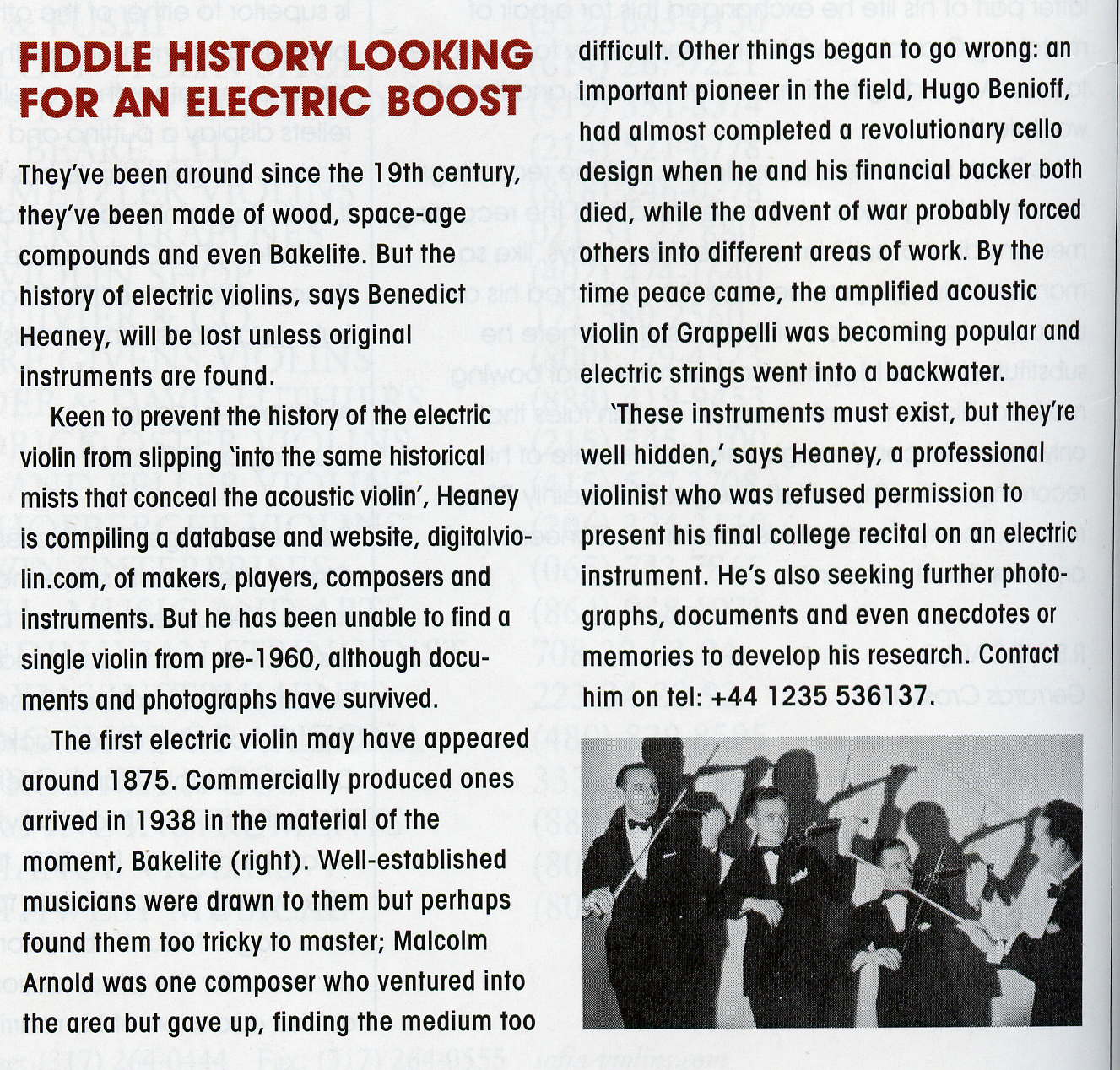

Local press and television picked up on the story lending help to the search with articles in The Oxford Times, Abingdon Herald and BBC Oxford News.

The international publication, Strad Magazine also lent their support with a small news article published in the October 2000 edition.

Despite concerted effort over the course of the next five years, the instruments evaded being found. Then, a small online shop in New York listed for sale one of the oldest electric violins: a “Rickenbacker” Electro Violin. Founding member of The New York String Service’s Musurgia outlet, Steve Uhrik, specialising in fine, rare and peculiar musical instruments finally had presented the possibility of some answers. Strad Magazine published news of the find and Uhrik revealed more instruments and information pointing to the survival of perhaps the very oldest electric violins ever to have been manufactured.

With the rapid growth of online markets and auctions, since 2005, proof has been found that a few of these very old electric violins have survived in full working order. Also, in the past two decades, what started out at a dead-end with a story of total loss and mysterious disappearance has turned in to an exciting adventure with many sprawling paths to follow, a fullness of history and many more people turning to the electrified violin. Without any doubt we have reached a point where the biggest musical instrument manufacturers successfully sell electric bowed string instruments all around the world and the established centres of music education have begun to actively encourage exploring the medium.

The original website, Digitalviolin has now been amalgamated into the broader work of Deltaviolin and appears here in this website as a much augmented, revised, edited and hopefully improved document. There is still much work to be done. Hopefully this format will allow for much more exploring and unearthing!