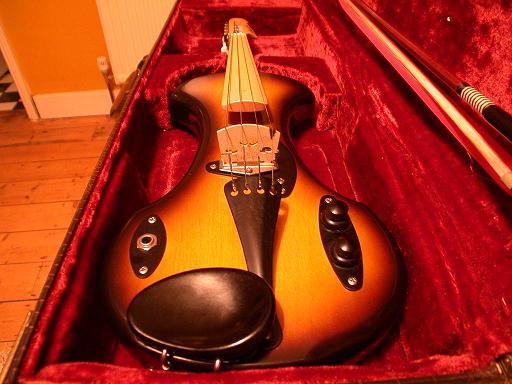

With the unique 1958 production prototype Fender Electric Violin in mint condition and perfect working order, Ben Heaney ‘takes it for a spin’ putting it to test and using it to make a recording of Telemann’s Fantasia #7.

In the 1950s, Fender had aimed to build ‘an improved electric violin’ which could be ‘mass produced economically and with a very high degree of predictability and uniformity of tone’. Another objective of his invention was ‘to provide an instrument having great sensitivity and fidelity’ and be ‘adjustable in order to compensate for various conditions during use’ (Leo Fender, US Patent 3,003,382). If he succeeded in this endeavour then his electric violin should be a fine and safe choice to use to play any violin music. Considering though that by late 1958 Fender had apparently lost interest in the electric violin, had received serious criticism from a few players for his violin invention and that no one knows for certain if the only two Fender Sales orders for one hundred violins each were filled; one massive question is raised. Did Leo Fender, designer of some of the world’s most iconic guitars, who set the standard for electric bass guitars and formed the basis of amplifiers in the 1940s still relevant today simply fail to make a good violin?

The only way to really discover the answer to this crucial question was to play the instrument. Whilst it was tempting to turn to modern and new musical forms and genres to test its validity as a fine instrument, there was more interest to discover how it fared with a different type of ‘new’ music.

The “Twelve Fantasias for Violin without Bass” date from 1735 and are considered good examples of baroque music. ‘Displaying an original devotion to music’ with ‘elements of the sonata, the concerto or the suite taken up’, as pieces for Violin they encompass ‘all the playing potentialities of the instrument'(Hausswald, editor Urtext edition).

An interesting challenge then, to pit the Modern electrically amplified violin from Fender’s workbench against music written for a violin so much older and seemingly so very different. There are however some striking parallels, beyond being instruments with four strings played with a bow and without frets!

At the time of their writing in 1735, the violin as the traditional looking instrument we know so well today was only just reaching a state of perfection, it was therefore still quite new. The electric violin has been developing and evolving now for over a century and as such is equatable in newness to the violin of the early 18th Century. The greatest names that were to become the Giants and ultimate standard of violin making, Antonio Stradivari & Giuseppe Guarneri were both still alive and active. They had developed an instrument that in the early 18th Century had become fully integrated into the family of instruments involved in ‘a new musical era’ and the ‘flowering of violin music, established by Corelli was very rapid’ (Nicholas Kenyon, Ed. Dominic Gill “The Book of the Violin”). The electric violin is arguably now a firm member of the family of instruments. It is certainly well integrated in to many non-classical styles around the world and appears only to be finding further and more varied use, including in the classical profession as time passes.

A small sample of the first test results in the form of a recording of the 1st movement “Dolce” of Telemann’s 7th Fantasia can be found on Deltaviolin’s soundcloud. There you can hear this unusual and super rare instrument played unaccompanied, possibly for the first time ever.

It is a very challenging violin to play. It is heavy and obviously different in tone to a purely acoustic violin. However, there is something beautiful and unique in the sound and it works. At the very least, for those interested in finding the right violin or electric violin for their needs you have some insight in to what Fender produced and possibly what was being aimed for…

tbc