STROH

HORN-VIOLINS

Since 1899…

For many years the violin related work of John Matthias Augustus Stroh, Sir Charles Algernon Parsons and others has gone unexplored, almost unnoticed. Where mentioned then, only briefly. Parsons’ name, along with more than a few are almost exclusively left out in discussion of Horn Violins. These being quite surprising discoveries to date. However, the individuals working at this chapter of violin history were living during the important bridge between the violin before and after the beginning of the 20th Century. The move from acoustic to electric. So much has happened! These were people arguably responsible for the most unusually novel solutions to problems associated with the violin family, and their work possibly ensured the violin surviving in the Modern world. Many instrument designs and concepts now a century old have been either consciously or unconsciously developed and refined in the world of electric violin today. Many claims of innovation prove erroneous in the light of this work, so much of the time the so-called new concept is old hat.

Finding any example of a Stroh-Violin or Horn-Violin though is a difficult thing to do. Whether these violins are satisfactory musical instruments seems subservient as they were once used a lot. They were definitely common place in the recording studio for two decades, at least. During this time they were the preferred instrument of choice by the most important recording companies. Normal violins had actually been discovered to be too weedy and feeble to make a good enough impression.

Evidence of the work of Stroh, Parsons and others is found scattered over a considerable number of years in amongst different patent classifications, magazines, books and newspapers. In the case of Parsons, encyclopaedias record that his work in the field of direct current generators was revolutionary. He was responsible for the first practical steam turbine engine and his invention of high speed-dynamos revolutionised ship design. These are well known facts. Of course, all of this means Parsons was an important Engineer, as was Stroh, but can he be said to have succeeded in bringing a practical working object to the needy violinist? Not in a directly simple way, and not nearly with as much clear success as John Stroh managed in the same field. Memory does not appear to really recall any other information other than there being Stroh Violins. The object of invention in question is called a number of things from Stroh-Violin, Stroh-Viol, Horn-Violin, Phono-Fiddle and a Trumpet-Violin. Others would call it a curio, a joke or merely a gimmick but they are wrong. It is this violin by Stroh that is the focus of attention in considering how radically different things were at the time of their invention and just how drastically those things were then going to be. For reasons of clarity other names important to the whole story have to be omitted. Their work is better understood after considering how Stroh reached new ground and very much facilitated the electric violin with the result of his invention. Also, it is noted that Stroh’s work in a wider context comes after the inventions of this type of musical instrument by Ferdinand Hell; Sewell Short; W.E. Newton and N.G.I. De Laphaleque. They are not discussed here. Their instruments are integral to the whole process of change but have probably not been used nearly as much as Stroh violins by professional violinists.

*

Great stature is attached to very few people. Being an inventor of any worth, let alone to better the work of the Great Italian violin makers is no mean feat. Stroh is certainly no Stradivarius, Amati, or like any other significant violin maker. He was brilliant and maybe the first open-minded enough person to put themselves to task presenting a violinist with the all important improved object. Stroh attacked the problem from the ground up, solving it almost from scratch. Stroh’s work is refreshing to the senses and at the very least, stage one on a journey that had not been trodden with such determination for over five hundred years. Stroh was about to rock the boat in a profoundly significant way. In a way, the boat took on too much water and sank. You can only say this though if you have played one of these violins, or heard it acoustically, live. There had obviously been previous attempts but none as thorough, and certainly none that were so successfully played by classical and popular violinists in so many numbers.

Stroh’s violins are wacky, wonderful members of the musical instrument family but are completely serious too. This, whether liked or not. As a prestigiously appointed Royal Engineer, Stroh was largely responsible for bringing the recorded and played back sound to England but he also found himself focussing on one of the sound sources being recorded. The reason and discovery was that one violin can only be so loud before the task of creating more becomes futile. The recording devices were faulty in this respect but had to be used and thankfully too, for reasons of musical heritage.

Both the great names Edison and Berliner had noted the violin’s weakness in the sound department. Berliner went as far as patenting violin inventions capable of emitting a louder sound in 1881. Stroh’s work was much more radical in finish.

Before the acoustic recording device, there had never been the need for a type of bowed stringed musical instrument that could project such a powerful sound. Although this had always been worked towards and was going to be an inevitable straw that broke the violin’s back. Importantly, Stroh was an engineer not a violinist. For the violin to survive beyond 1900 it had to fulfil a huge demand. The Recording Industry was taking off and there was a rapidly growing audience. Stroh was not inhibited by life-experience based on knowledge and understanding of traditional violin making and besides, the market for “canned” music wasn’t caring much for instruments that couldn’t be heard. In the days of acoustic recording there was no television and the performer was more and more becoming known by their music only. Kubelik, a violinist of some standing, first became a recording artist in 1905 and was amongst other violinists who certainly changed with the times. It has not been possible to really analyse whether these violinists accepted the Stroh’s violin as a necessary evil graciously, or whether anyone believed it was a step towards a better violin. There is too little directly referenced evidence to make either definite conclusion.

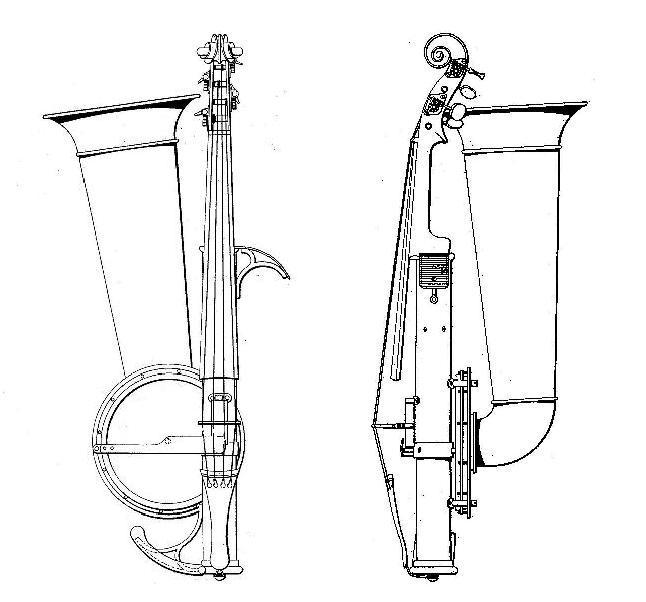

The mainstream violinists riding in the wake or crests of Paganini and the Great Italian School could not envisage the first twenty five years of the 20th Century. At the close of the 19th Century, after nearly four-hundred years of massively successful and fulfilling use, the body shape and construction of the violin proved too feeble to make a clear enough imprint on the recording device. The following quote is taken from Strohs 1899 patent claim for the violin intended to solve the problems associated with recording the sound of a violin. “…the body of the violin with its sounding boards is omitted, and the head, neck and bridge, tailpiece and strings of the violin are mounted on a suitable frame made of aluminium, wood, or other suitable material.”

It is clearly characterised by a trumpet-like bell, or horn attachment. Some designs had a second much smaller horn which angled towards the player allowed them to hear the sound directly. Just like that, the problem in the recording studio seemed solved. This first real breakthrough for Stroh came because the mechanism used for the violin worked in harmony with the horn, membrane and stylus system being used by recording machines. Stroh simply worked the recording process in reverse i.e. what a recording does to the stylus in playback mode, and a new violin sound was born.

Observe the immediate parallels that exist between a Stroh and Stradivarius violin by their mechanism.

The friction of rosined bow-hair working perpendicular to and against the strings causes a rocking motion of the bridge. At this point both a Stroh and a Stradivarius violin are the same, having a “normal” bridge. Beyond here the world of violin making holds two very different stories. Stroh definitely chose something quite different but only because the materials were there to be used. Whereas Stradivarius crafted organic materials, Stroh had synthetic materials to work with and so naturally used them. Disregarding the choice of materials used and how they are employed Strohs and Strads are both violins. The rocking motion of the bridge created by a vibrating string in the case of the Stroh violin vibrates a diaphragm/membrane. In the case of Strad the bridge vibrates delicate plates of wood. This wood is thinned to less than 2 millimetres in thickness in parts. The line between what constitutes a diaphragm/membrane or plate is thin and in some inventions very ambiguous. The whole process, in either Strohs or Strads case can only be properly heard as sound when the whole device is attached to a sound amplifying device. In the case of Stroh, the thin end of a trumpet horn. For the case of Stradivarius the very shape of the hollow body and construction. Stroh?s violin is a direct and simple way to amplify and project the music of the bowed string. In every way the concept remains soundly “of the violin” but in every other way it appears out of this world. Stroh only needed to retain that the instrument be able to be played by professional violinists.

” When, about three hundred years ago, some daring spirit cut down a treble viol and converted it into a ‘violino’, or little viol, he probably never dreamed that he was giving to the world an instrument that should ever afterwards rule as king in the vast domain of music.”

(Donovan, 1902)

At some point the violinist, composer and audience would demand something more.

*

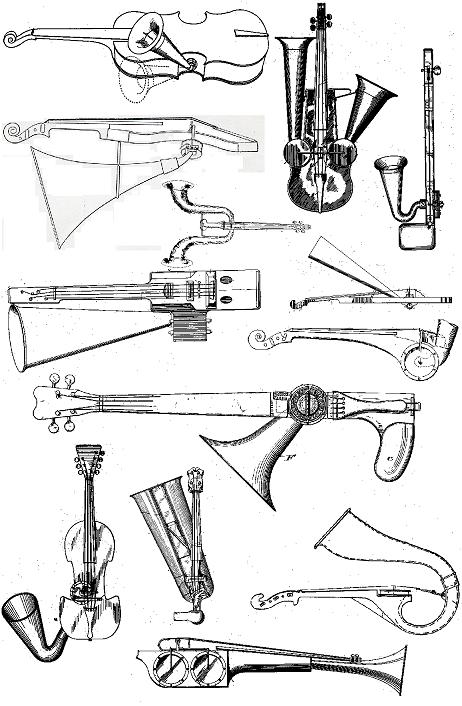

Efforts made to improve the sound of the violin have been constant since it was first invented. Undeniably, every aspect of its playing method and construction technique has been scrutinised over the years, with slight adjustments being made at each step of the way. What we naturally have is today’s highly developed musical instrument. Stroh’s work reinforces this opinion and should therefore be worthy of more attention and further experimentation. Terribly enough our chances maybe already be lost. Any further, deeper examination requires working instruments and they are rare. Rarer still are the subsequent makers and opportunists Stroh’s work inspired. These other makers of violin appear here in chronological order of Patented invention and are pictured together above for the first time:

1904 Stella E. Griswold, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA

1904 & 1906 Sir Charles Parsons, Northumberland, England

1907 Percy R.J. Willis & Irvin A. Northrop in Surrey, England and Ohio, USA

1908 Peter A. Amundsen, Wisconsin USA

1908 Samuel W. Buerklin, Oklahoma USA

1908 Charles Benton Gillespie, North Dakota USA

1918 Walter F. Young, Wisconsin, USA

1922 Loren C. Bond, Washington, Columbia

1922 Glenn D. Bothwell, Michigan, USA

1922 & 1923 John Kalaf Jr., Missouri, USA

1922 Frank J. Kummeth, Minnesota, USA

1926 Earl Pagett, Kansas, USA

1927 Benjamin A. Askelton, Saskatchewan, Canada

1928 John Emil Hillenbrandt, New York, USA

1931 Jose Ma Pena, Tampico, Mexico

1931 Toy Thrasher, Mississippi, USA

1949 Harry Lewis, Texas, USA

These instruments, appealing or not, appeared during the establishment and rapid growth of the recording industry and attempted to bring the violin up to date with the needs of a modern-day musical environment. To the traditionalists Edison, Stroh and Parsons were Scientific Engineers with no hope of a workable violin related idea, probably. Hopefully they worked unbothered by any such blind-criticism. But, non-interest in their work was certainly their ultimate punishment for venturing near the Art of violin with such ludicrous looking objects. Compared with the classical design these “fiddles with horns” are unwieldy looking. To most serious violin lovers, they just don’t have the same sartorial eloquence.

These instruments, appealing or not, appeared during the establishment and rapid growth of the recording industry and attempted to bring the violin up to date with the needs of a modern-day musical environment. To the traditionalists Edison, Stroh and Parsons were Scientific Engineers with no hope of a workable violin related idea, probably. Hopefully they worked unbothered by any such blind-criticism. But, non-interest in their work was certainly their ultimate punishment for venturing near the Art of violin with such ludicrous looking objects. Compared with the classical design these “fiddles with horns” are unwieldy looking. To most serious violin lovers, they just don’t have the same sartorial eloquence.

This argument sways more heavily than the instrument’s objective worth. At the time of their initial use, Stroh’s violins were received well for their tone. They existed possibly exclusively in the recording studio scenario, but despite this some sincerely liked the sound however far removed from a violin it appeared.

“The G string is a dream. It possesses the deep rich quality of a fine ‘cello A, but there is no unevenness in the strings. The harmonics are loud and pure, and what is of great importance is an entire absence of ‘scrape’ … And it will, I venture to predict, in spite of prejudice, ultimately be recognised not only as a triumph of creative skill, but as worthy of taking its place with those instruments which depend for their effect upon attuned strings.”

D. Donovan (Strand Magazine in 1902)

Consider too the fact that these violins did the job better,

“Violins frequently transmogrified into strange devices with tiny horns instead of proper bodies – these Stroh fiddles were heavier and scrawnier sounding, but at least they were loud…”

Broadcasting spread music further than ever before which in turn built up the excitement for a live performance. Today it is completely impossible for the best performing artists to play to everyone who would like to hear them play, but a vast number of people can enjoy the next best thing by listening to a recording. Without the pioneering work in the development of the phonograph in the United Kingdom, Europe and the USA, and without Stroh’s work with the violin; a vast number of recordings of violin music simply would not have existed. And, therefore it would be an instrument not as widely heard. Or, is the bowed string more fundamental to be sidelined so easily?

“Surrounded by these fortuitous gadgets of sound concentration, the lot of the recording artiste in those days was hardly an enviable one. Illustrative of the dilemmas is a newspaper cutting of December, 1904, which announces: Kubelik has made two records with his own Stradivarius, not a Stroh.”

Joe Batten?s Book, 1956

Very soon after the acoustic recording industry was born and the technology and instruments became commercially available; the so-called “electric” device made its entrance. Electric devices did not just bring about the demise of acoustic recording and playback devices; they effectively brought an end to the use or need for a violin with a trumpet-horn attachment. The end regardless of whether Stroh, Parsons and others might only just be beginning to perfect their designs and mechanisms. The electric microphone effectively started a battle for supremacy between the traditional classical acoustic violin which could now be heard by means of subtly placed microphones and the electric violin which had to start completely from scratch, no guide, and no tradition. There was now the opportunity, albeit starting hundreds of years behind the violin for something entirely new.

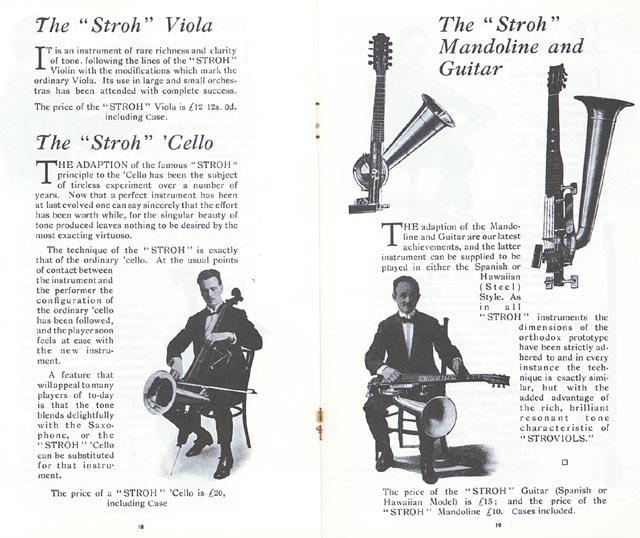

EMI’s move to embrace electric recording and playback equipment in 1925 destroyed the need for Stroh’s bowed stringed instrument work. With electric microphones the sound world altered completely and the traditional classical acoustic violin was given another chance. Within a few years the violin with trumpet horn attachment became as good as extinct. Stroh Violins were at least loud and cheaper than hiring a whole orchestra. Certainly, without Stroh less violin music would have been recorded, fledgling companies just don?t have money to waste. Can Stroh-violins be considered an advance? Instruments of Stroh are found nowadays only in a few museums and in some private collections, very rarely turning up in junk-shops. The internet has turned up a few original units for sale and also fascinating documents and catalogues revealing a whole family of bowed or plucked stringed instruments prefixed with the name Stroh. These facts couple with the use of Stroh being contemporaneously associated with Popular Folk music leads this aspect of violin history away from the development of the Classical violin. It was, as can be seen to be a stop-gap whilst technology improved.

Reference to the first electric inventions for music can be found quietly developing, progressing and unfolding through the patent books whilst Strohs established themselves in the studio. The inventions in question had only just achieved any notable attention by the time of Stroh’s death in 1914. Relying on a few written accounts we learn that Stroh’s work continued after his death through the family until 1925 when George Evans, violin maker took over the firm?s address. As far as the buying public were concerned, in 1931 the violin-with-horn-attachment was still in use. By 1943 the company listed as manufacturing violins at the original Stroh address changed to “Mechanical Engineers” and the Stroh-violin story was almost over. For the electric violin, this was just the beginning…